Student Symposium Project

Anthony E. Padget-Gettys

Tabletop Role-Playing Games: A Unique and Deserving Narrative Form

Tabletop Role-playing Games (TRPGs) exist in many forms, the most famous of which is Dungeons & Dragons (D&D). Both a game and a storytelling form combined, TRPGs have been around for decades and have recently seen a renaissance in popularity. Despite this renewed popularity, and long-lasting status, the form has received little academic recognition. Thus, in this project, I have taken to proving that the TRPG is a unique narrative form, and one deserving of more scholarly attention, by highlighting and exploring the form's distinct elements. Furthermore, I approach this goal via a primarily narratological investigation, meaning the systematic study of narrative and story. Nonetheless, I dip lightly into TRPG history and sociology as well.

If you are completely unfamiliar with the TRPG as a form, and thus may have difficulty even visualizing what this form looks like in action, I suggest watching this short Vox YouTube video first:

Albeit D&D-specific, while my work is applicable to many TRPG systems, this video does a great job of acting as an introduction to the TRPG. Additionally, this video touches on some ideas that I will be discussing as key to the form's uniqueness.

A note: This work originates from a year-long honors thesis project. Thus, as can be imagined, not all of its 250+ pages of discourse can be given here within this webpage. Nonetheless, below I summarize a large number of the major ideas and thoughts of my TRPG scholarship.

Oscillating Fabulae

One of the most immediately obvious unique features of the TRPG is its being split across two fabulae. A fabula is a layer of a story. For example, if a character within a novel begins telling a story themselves, that secondary, deeper story is on its own fabula level, with the outer story of the character telling the tale being a "frame story." The acting out of a TRPG story happens on both the "table fabula," or the layer representative of real-life people, often seated around a table playing the game, as well as on the "storyworld fabula," or the narrative world of the players' characters, where a more traditional, albeit collaborative, improvisational, and affected-by-game-mechanics, story is being told.

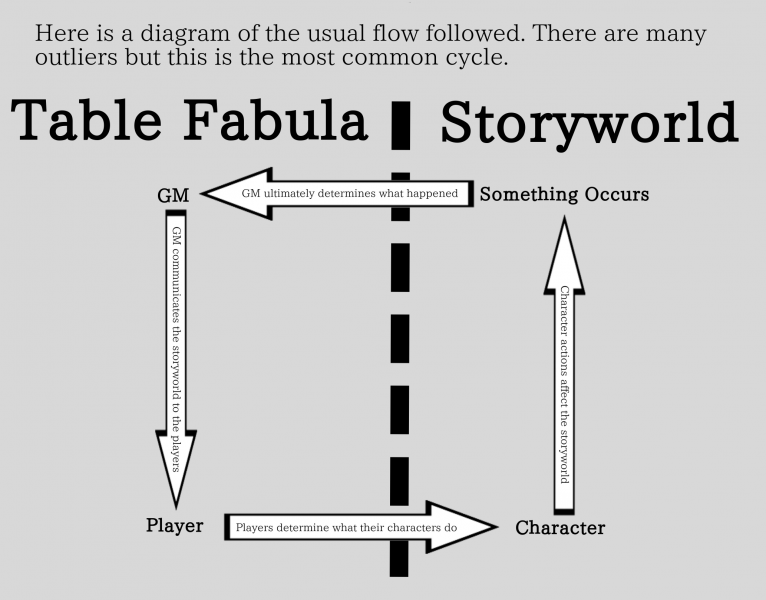

These fabulae are constantly in interaction with one another as players and game master (GM) (sometimes called the dungeon master (DM)) oscillate between which of the two they are operating on. The table fabula holds all the real-life, player-player conversations, as well as game mechanic discussions and dice rolls. The storyworld represents the, often fantasy or sci-fi, narrative world being crafted and "played in" by those involved. When something is occurring in the storyworld, the GM will describe it to the players (storyworld → table fabula). The players will then interpret that information for their characters, determine what their character will do, and announce that their character does this (table fabula → storyworld). How successful the characters' actions are is often determined by a dice roll, but nonetheless the characters, at the behest of the players, now affect the storyworld. This success, failure, or general storyworld affecting, will then be described by the GM to the players (storyworld → table fabula) and so the cycle continues.

Nearly every aspect of the TRPG storytelling form is affected by the fabulae's interactions, some of which will be seen below. However, before moving on, I want to make one statement clear: both fabulae make up the TRPG experience. One may be tempted to discount the table fabula as but an avenue to the storyworld fabula, and consider the latter to be the whole narrative. While the storyworld fabula does represent a more conventional narrative, the table fabula is key to the TRPG form. Not only does the table fabula hold the game rules that dictate the storyworld fabula's occurrences, but it itself contains much of the emotion and memorable moments that make up the overall TRPG narrative. When a high-intensity moment is met with a crushingly low or miraculously high die roll, the emotional excitement is unmatched. We will discuss dice further below, but, for now, it is simply crucial to recognize that the table fabula, with its rule concerns and dice rolls, is key to the complete TRPG narrative. After all, speak to any TRPG fan about memorable moments from game sessions and they will almost always recall an intense die roll as part of their thrilling retelling.

Shared Imagination

Practically, [descriptive passages] help the imagined world of the fabula become visible and concrete. They make it possible to participate in the imagination of someone else.

— Mieke Bal, Narratology, pg. 26

Considering the need for conversation, in both the form being collaborative and the need for the players and GM to describe storyworld occurrences, it is no wonder that clear communication is crucial to this form. The use of descriptions is especially necessary in the TRPG form, as the vast majority of the storyworld fabula exists exclusively within the TRPG group's shared imagination. This term, pulled from narratologist Mieke Bal (above), represents the mutually understood storyworld as it exists. Generally, the GM is in control of most storyworld descriptions and is generally responsible for the assurance of a solid shared imagination among the group via descriptions, explanations, the presentation of battle-maps or other visual reference, or whatever other tools the GM finds useful for assisting with the shared imagination. Without a consistent imagined storyworld between the collaborative players involved, the narrative can easily fall apart. For example, say one player believes that they are on the opposite side of a room from another, meanwhile the second player believes they are next to each other. When player two states that their character is going to punch the first player's, the difference in their shared imagination causes one to believe this is possible while the other believes it is not due to their being so far away. While this is a minor example, and thus one that would be quickly solved by the description of where people are being re-discussed or clarified, it nonetheless highlights a common way in which a difference in the imagined storyworld can start to break down the narrative. This is why the shared imagination is so crucial. This is why, in moments that rely more heavily on precise measurements, such as a battle, concrete visual aids are usually relied on to ensure the maintenance of the shared imagination. While this example plays more into the wargaming origins of the TRPG, utilizing battle maps and tokens/miniatures, it is still useful for recognizing how important the shared imagination is for the storyworld narrative of the TRPG.

Supreme Freedom

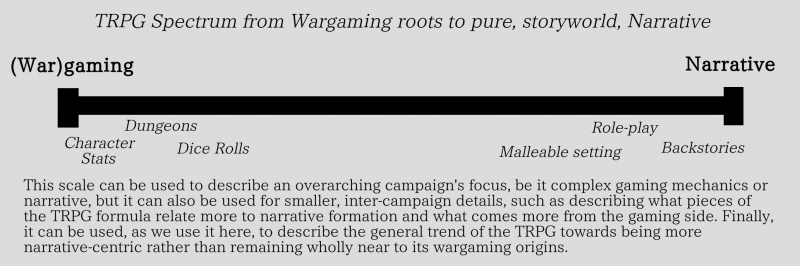

Over time the TRPG has evolved in a general trend towards more narrative focus and more player freedoms. The TRPG had its start in tabletop wargaming and thus originally has a much higher focus on combat. Additionally, the early days of the TRPG were much more restrictive with what a player could do. For example, while the earliest editions of D&D mentioned an ideal of being able to play whatever you wished so long as you started out weak and thus could grow strong overtime while playing, the very same early D&D had stipulations such as this one, told to us by Jon Peterson: “‘Dwarves may opt only for the Fighting-man class’ and similar restrictions apply to elves and hobbits” (Playing at the World, pg. 141). Luckily, as time has progressed and various TRPG systems have evolved, the form has generally trended towards actualization of its early ideals of extreme freedom and openness of choice. In a contemporary system, like D&D 5th Edition, far more official races and classes exist, without any limitations on the mixing of which races can play what classes. Furthermore, with the emphasis of promoting player freedom and creativity found in contemporary D&D and other systems, the world of homebrew, or fan-created content, has flourished. Considering the expanded number of choices seen officially in long-evolved systems, combined with the extensive world of homebrew classes, races, and more, the options for character creation and customization become practically infinite. Plus, that is with only discussing the game mechanics involved. Two characters could use the same class, race, items, etc. and still be completely different due to the personality and backstory injected into them by the player. With that in mind, the choices span into the truly infinite.

However, player freedom is not only existent in character creation. The TRPG is a collaborative form: the GM may be behind the description of the setting, the preparation of some trap or dungeon, and may be the voice of all non-player characters, but the players still control their player-characters, and said player-characters are the TRPG version of protagonists. As protagonists, they have a lot of agency. And, as entities controlled by various players, they have literal minds of their own. Thus, a player can state that their player is doing whatever they wish, and as they are the one in control of said character's actions, it becomes a reality in the storyworld (assuming GM, or die-roll, approval). The players are the driving force steering the storyworld narrative, deciding how to tackle problems or where to go in the first place. While what a character does must be within reason, meaning a player who has a low-level character cannot simply state that their character "slays a dragon," they have to go through the motions to do so and are likely to fail dependent on the die rolls (and character bonuses to said rolls) involved. While a player-character cannot simply do anything, as they are held back by realism, they are capable of attempting anything. Jennifer Grouling Cover gives an example surrounding an orc encounter saying: "[The GM] had planned what would happen if we defeated the orcs through battle and what would happen if the orcs were allowed to pass, but the actual pathways in the adventure were left up to the party [or group of player-characters]” (The Creation of Narrative in Tabletop Role-Playing Games, pg. 31).

Players can do anything, so long as their character succeeds and the outcome is possible within the setting. A key element which sets the TRPG apart from its oft-compared forms, such as the gamebook or a computer role-playing game (CRPG), is that the TRPG is actually being made in live time. While a CRPG may be played in real time, the player is simply engaging in pre-made code. Any choices made in the CRPG must be choices allowed within the game's code. Meanwhile, thanks to the TRPG player being in direct communication with the setting designer, the GM, they may simply ask if they can do something, even if it is outside of the usual game mechanic's rules, and they and the GM will decide how that thing is attempted and plays out. This allows for legitimate freedom of choice, as opposed to the pre-made branching paths offered by Choose Your Own Adventure books or CRPGs. TRPG developers recognize that they cannot create rule systems for every encounter or choice, and, thus, they expect that the GM and players will be able to decide how an unruled-on interaction occurs, likely basing their solution on existing rules for similar actions.

Thus, the TRPG offers infinite character creation choices and infinite in-game character choices. This heightened emphasis on freedom has accompanied the TRPG's general shift towards a narrative focus. While, as stated above, the TRPG had its start in wargaming—and still very much holds on to many of those elements in combat—the TRPG has shifted towards more interest in storytelling and in role-play, rather than in battle. Fighting may still be common in a TRPG campaign, but narrative elements have become the primary draw to the form for most. Of course, there are still those who prefer the TRPG's wargaming-related elements, and there are some TRPG systems that still heavily emphasize those elements, but the general trend over the decades has been a shift towards narrative interest. Mostly gone are the days of endless dungeon crawls and extreme good triumphing over extreme evil, and come have the days of in-depth role-play, overarching plot intrigue, and more nuanced characters and story.

Role-play Immersion

For the game to work as an aesthetic experience players must be willing to "bracket" their "natural" selves and enact a fantasy self. They must lose themselves to the game. This engrossment is not total or continuous, but it is what provides for the "fun" within the game. The acceptance of the fantasy world as a (temporarily) real world gives meaning to the game, and the creation of a fantasy scenario and culture must take into account those things that players find engrossing.

— Gary Alan Fine, Shared Fantasy, pg. 4

Much like the reader may become lost in the passages of their novel, losing sense of the book in front of them and simply being completely engrossed in the story on the page, the TRPG too creates a sort of engrossment through role-play and gaming elements. This engrossment is generally referred to as immersion, at least for the storyworld. When we think about immersion in the TRPG, we usually are referring to the storyworld, but it is important to recognize that the thrill of the gaming elements can be immersive all on their own: forgetting the world around you as you become enthralled in the game mechanics of the table fabula. This table fabula immersion is important to recognize, but immersion is most often used referring to role-play due to the necessity of portraying a character, and thus a natural interest in investing one-self wholly in the character whilst playing. Of course, this immersion is complicated by the two fabulae, as one is constantly having to stop role-playing in order to roll a die or address a game rule. Nonetheless, the TRPG's smoothness of transition between fabulae, assisted by many immersion-helping tools—such as the use of the second-person point of view to address a player as their character and thus guide them into character—leads to there being few issues with the breaking of immersion stemming from the fabulae.

Nonetheless, while the benefits of immersion may be clear—realistic characters, heightened investment, engrossment in the story, deepened emotional connection to characters and events, etc.—there are negatives accompanying this as well. For one, there is the TRPG cardinal sin of metagaming, or the application of player-knowledge to the character without the character having reason to have access to said player-knowledge. A player may know the GM is rolling a dice and thus there may be trouble afoot, but their character is not aware of the GM and their dice, and so the player should not have their character take action based on this table-fabula-exclusive information. Or, perhaps a player, sitting at a table (or in a remote group call), overhears what another player's character is doing in a place their character is far away from; obviously player-knowledge and character-knowledge would thereby differ. It is then the player's job not to allow their own knowledge to affect their character's actions or thoughts, as said character has no access to this knowledge. Metagaming is a common issue in the TRPG, and as such is a well known one that is often avoided or addressed with ease, but it is nonetheless a drawback to come from the form's multi-fabulae-hood and role-play.

Some Key Benefits & Drawbacks of the TRPG Form

Of all the key thoughts or sections of the overall thesis to summarize, this broad category is the hardest to do in both a concise and thorough manner. So, to spice things up and to save your poor scroll bar, ever-smaller it grows as I type, we shall take to bullet-pointing. Have no worries, the whole thesis is linked at the bottom of the work should you want to look into any of these ideas more deeply.

- Only Onwards: Due to the live-play format of the TRPG, time within the story must only progress forward. There are plenty of pauses or slow-downs in time as a group plays, generally to address the system's rules or roll a die. Nonetheless, this does not break the requirement that the TRPG story must be told chronologically. The live-play form means that a TRPG story cannot easily utilize substantial flashbacks or time-travel. If either of these was utilized and a player's freedom of choice or the randomness of dice were to make substantial changes in the past of the story that would affect the story's present, then the game's internal logic would be ruined due to the inability to "go back and edit." There is no returning to a previous chapter to edit in the TRPG. The form is live and improvisational, and thus comes the drawback of needing to tell chronological stories (although, most stories in other forms tend to be purely chronological as well, so this drawback is ultimately quite minor).

- Inability to Perfectly Pre-plan: Another drawback that the live-play and improvisational form brings to the TRPG comes in the inability to perfectly pre-plan events. A GM will do a lot of preparation for a session—preparing maps and expected plot lines—but, thanks to the extreme freedoms and agency held by the players, the GM cannot truly predict where the story is going. They may try to plan a battle locale that is very thematic, but if the players choose to avoid the battle, wait out the enemy so as to not risk fighting on the enemy's turf, or even do something that changes the appearance of the setting the GM had created, then the GM's assumptions of what would happen will not be met. Even if the players do as the GM thinks they will, the inherent randomness of dice rolls can lead to unexpected and unprepared results. This is why improvisational skills are key for both players and GMs. One may believe this is a substantial drawback, but the excitement and uncertainty created for both players and the GM out of the unknown future of the story is thrilling. The TRPG generally favors heightened emotions brought about by uncertainty over the thematic opportunities more easily available to, say, a novelist or film writer.

- Inherent Randomness of Dice: Many would consider the randomness of dice to be, while thrilling, a problem in telling a serious story. However, the dice bring realism into the story, as even the most skilled people can fail. While being more skilled at something in the storyworld will lead to better bonuses being added to your die roll, there is still a chance of rolling poorly—even the master swordsman can fumble a strike. Similarly, even the novice can land a lucky blow. In other forms, such as an epic film, if the hero were to drop their sword in an important battle, then the film would immediately become parody and no one would take the scene seriously—"How could the hero drop their sword at a time like this?!" Meanwhile, in the TRPG, if a poor roll leads to a fumble like this, the form does not become parody, and, rather, the realistically possible fumble heightens the intensity, as now the player must figure out how they are going to recover and still win the fight. In these ways, the randomness of dice becomes a benefit rather than a perceived drawback. Furthermore, considering the interest of many, more conventional, forms in uncertainty—see the Modernists' interest in spontaneity and randomness, for example—the TRPG achieves, and makes elemental, an idea many other forms can only lust after.

- Malleable Setting: Another key benefit from the TRPG's freedoms is the players' abilities to shape the setting with the GM. Player choices and actions, thanks to their agency, will affect the happenings of the overall setting, and will do so in live time thanks to their direct and actual-time interactions with the GM: the setting constructor. The TRPG world is not simply one that is played in; it can be shaped by the players in profound ways. This is a key allure to the TRPG form, as this agency is missing from most of our real lives. While we cannot easily affect our vast world, our characters' enhanced agency, as they both have extreme freedoms and are protagonists, help us, as D&D co-creator Gary Gygax put it, "become super powerful and affect everything."

- Struggle for Interiority: Much like a novel adapted into a movie, the TRPG loses the ease of showing interiority. While the novel can simply say what a character is thinking, and a film may employ voice-over to do the same, the TRPG struggles to showcase interiority. Like actors without the trope of asides to the audience, the players must act out their character's interior feelings without telling them directly. Sure, a player could just state how their character is feeling or thinking, but this is generally shunned as presenting metagame knowledge to the other players and as an avoidance of role-play. A player can attempt soliloquy, but these are rarely seen in the TRPG, so instead actions or dialogue in role-play are used to convey interiority. While harder than simply writing how a character feels on a page, the nuance of this practically required show-don't-tell approach to interiority can build more compelling characters and heightened emotional attention.

- A Rare Form of Dramatic Irony: One of the unexpected benefits of the TRPG is the existence of a rare, and wholly internal, form of dramatic irony. There are all sorts of dramatic irony prevalent in the TRPG form, but for this short summary I shall simply point out one of the more interesting examples: an example which stems from metagaming. While the application of player-exclusive knowledge into a character's thoughts or actions is a problem, the existence of that difference of awareness creates an internal sense of dramatic irony. The player knows something that the character they play does not. Like the actor in the play who cannot use their knowledge of scenes their character was not in to affect their character's actions, the TRPG player must not allow player knowledge to steer their character. The key difference in this comparison is that the actor is following a script, and thus has little danger of allowing their knowledge to affect their character's. Meanwhile, the TRPG has no script; it's future is entirely uncertain and is steered by character choices, and, thus, this dramatic irony is more pertinent and avoiding using meta-knowledge is more important. There are plenty of other examples of dramatic irony being modified by the TRPG's addition of the GM role, but this wholly internal irony between player and character is especially interesting thanks to its rarity in other forms, but its prevalence in the TRPG.

- Literal Character Growth: Many stories make character growth a central theme to their tale. The theme of bildung is popular because we like seeing characters grow: it is both compelling and establishes these characters as more realistic. The TRPG has all the usual ways of having character growth—through attitudes, learning, etc.—but further uses its gaming side to give literal character growth in the form of leveling up. As characters progress in a TRPG story, they will grow more powerful, more skilled. Depending on the system, they may gain experience till they level-up, may hit a milestone for leveling up, or may simply gain experience which they can spend directly on skills and abilities. This literal character growth helps make the bildung theme innately prominent in the TRPG form. Similarly, the collaborative nature of the party makes "found family" themes common, and many other TRPG elements bring in themes or tropes that are made more prominent, or interestingly modified, due to the form. While describing these all here would take too long, the character growth example is especially interesting, as it links directly to the unique gaming qualities of the TRPG narrative form.

- Logistical Issues: As a collaborative form, the TRPG runs into some obvious issues with scheduling and meeting. TRPG groups generally meet weekly, often for 3 or more hours a session, to play. This chunk of time can be difficult to work into one's schedule consistently, and thus, struggles with scheduling tend to be the demise of a TRPG group's consistency. Of course, like any long term collaborative effort, it is easily possible to maintain a group schedule; this is simply one drawback frequently encountered. It is true that a player may need to miss one session due to unexpected busyness or something scheduled at that time of higher importance, such as a doctor's appointment. Nonetheless, the session will generally go on, with the GM taking over that player's character and the other player's consciously making efforts to avoid much interaction with that character while their player is away. The GM may even make a reason for why that player's character has split away from the group to do something else for the time of that session. This latter example even points to a convenient capability of the TRPG: the ability to occasionally split the group and pursue multiple storylines at once. Take an example given by Jennifer Grouling Cover:

When Mary could not attend the Blaze Arrow session she decided that her character, Maureen, would go back to town. At this point her character entered an alternate plotline that none of the other characters had access to. Scott [the GM] talked with Mary separately to work out the details of what happened to Maureen in town while the rest of us were dealing with the orcs.

(The Creation of Narrative in Tabletop Role-Playing Games, pg. 32)

Popularity Boom

“When a new edition for a game like this releases, there is that flurry of activity, people get really excited about it and then, historically, that excitement has waned,” [Greg Tito, senior communications manager at Wizards of the Coast,] said. “The fifth edition has completely blown that model out of the water. With the release in 2014, it has grown and only continued to grow. Every kind of statistical model we’ve been able to to use from the history of ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ has been broken at this point. So, we are in uncharted territory.”

— Sarah Whitten, ‘Dungeons and Dragons’ has found something its early fans never expected: Popularity.

https://www.cnbc.com/2019/03/15/dungeons-and-dragons-is-more-popular-than-ever-thanks-to-twitch.html

While the above quote is only speaking to D&D 5th Edition, it, being the most popular TRPG system, stands in to represent the overall trend of the TRPG into the heights of popularity. Recently, Wizards of the Coast, the company behind D&D, reported that 2019 was the most successful year ever in D&D's 46 year history, a trend in increasing popularity that looks to continue. With D&D leading the charge, other TRPG systems, and the TRPG as a whole, has been growing in popularity, boasting millions of worldwide fans. This renaissance of the TRPG is assisted by many factors, a key one being the internet. The internet has led to the popularity of TRPG livestreams, podcasts, and video series. Through this, groups' TRPG campaigns can be shared with wider audiences. These shows have seen massive success, with examples like Critical Role getting over a million views on episodes and The Adventure Zone being adapted into a two-time New York Times Trade Fiction Best-seller, with their third graphic novel on the way. These adaptations and shows help grow the community by creating large audiences who can learn the form by watching. They also create examples for us to look at as, otherwise, a specific TRPG story is likely to only be seen by those playing it. But now these shows act like published novels to look to rather than simply analyzing the general form of the TRPG.

The TRPG's growth in popularity has also been assisted by the community's inclusivity, something it could not always boast. In the past, TRPGs were extremely male dominated, and often, as such, showcased a lot of misogyny. However, not only is the female player base growing rapidly now, but the TRPG's narrative and freedom focus has led to its adoption by many minority groups as a game where they can forge a storyworld without bigotry, or a place where they can explore themselves while having agency and freedom to do so. Having played in the early days of D&D, American-Dominican writer Junot Díaz said this in a New York Times Retro Report:

“This was a revolution. Being a bunch of kids of color—in a society that tells us we’re nothing—being permitted, under your own power, to be heroic, to have agency, to do the hero stuff, to take and be on adventures. There was nothing like it for us, it was very, very, very, very impactful.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATUpSPj0x-c

Now, even the companies behind TRPGs uphold an ideal of inclusivity for their communities.

There are many elements to help us realize why the TRPG has grown so much in popularity in recent years, or how or why the TRPG community has become so open, inclusive, and devoted. But, the important thing for us to note here, in our summarizing, is that the TRPG is growing as a form, accruing a larger and larger following. It also has a complex and interesting past and present sociologically. Considering the growth of TRPG stories, and the fascinating social aspects of the TRPG community or group, it is a disappointing wonder that we do not have more recognition and scholarship relating to the TRPG form. A form as unique and prevalent as the TRPG deserves much more academia and, being such a fun and popular form, it should have more players.

Why not take this strange time to try out the form yourself, remotely with friends? Services like Roll20 assist with playing online, and do so for free. And, with the 2020 quarantine, companies like Wizards of the Coast have been releasing content for free to bring people into this community and lend a helping hand in these constraining times:

https://www.dndbeyond.com/how-to-play-dnd

https://www.dndbeyond.com/quarantine

While in scholarship I prefer to discuss TRPGs as a whole, it is undeniable that D&D reigns supreme in popularity, and does so largely thanks to the ease of access it grants to new players: it is not a difficult system to learn. So, why not come join the TRPG community? Play a few sessions and see how you enjoy this incredible and unique form, it will likely surprise you. And, while you are playing—wishing luck from me to you—roll well!

To read the entirety of the thesis, from which I try to summarize some main points here, click the embedded link directly below and you will be brought to a Google Doc:

Note: This is the submitted 2020 honors thesis version of the project. I plan to continue refining, expanding, and exploring this work further. So, if you want to keep an eye on this work for future changes, see the contact information below. And, if you have feedback or comments, please do send them my way!