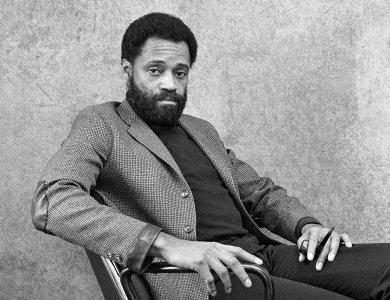

Melvin Van Peebles Changed Filmmaking and Our World

Melvin Van Peebles, avant-garde filmmaker-writer-performer and culture hero, was a member of the OWU Class of 1953, and an English major. He arrived here as a sophomore and was briefly involved with campus Greek life. His more consistent student interests, according to the few materials collected in university archives, involve his activity in AFROTC and in campus literary circles, as a couple of poems of his appear in the campus literary magazine, OWL.

Van Peebles served in the U.S. Air Force, moved to various cities to establish himself as a film director, and found repeated doors closed in his face due to the legal, economic, and social limitations of Jim Crow and a United States that was still in the early days of the Civil Rights Movement.

In response, Van Peebles constructed new doorways, becoming a self-taught film director and troubleshooting his way in France to a professional career as, first, an author of novels in French, and then as a filmmaker making French films.

His first film, The Story of a Three-Day Pass (1967), which he adapted from his own French novel and directed in France, allowed critics and audiences in the United States to finally “discover” and praise Van Peebles when the award-winning film toured here after its release.

His stunning, satirical film Watermelon Man (1970) was his first American-made feature film, but Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) is the film most frequently associated with Van Peebles and arguably his most famous work.

Not limited to filmmaking, Van Peebles composed music and wrote and performed songs on a number of albums. He wrote novels, plays, and many musicals. l Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death (1971) and Don’t Play Us Cheap! (1972) both ran on Broadway, where Van Peebles received multiple Tony Award nominations, and the two shows were nominated for the Best Book of a Musical category in their respective years.

Van Peebles’ Distinguished Achievement Citation from OWU is one of scores of awards and work credits. He was active as an artist and provocateur right up to his recent passing. And he somehow found time, amid his renaissance life, to be a devoted father and family man.

Yet, I am struck by the thought that his journey—at OWU and beyond—was marked by a continual sense of being made an outsider, of not being fully understood and appreciated.

I’m thrilled that space is being made to pay tribute to him, and in that same thought I wonder if even this mention is enough. I am not overstating to say that Van Peebles is an artistic voice that made other voices in the industry possible. Having lived a life that forced him to open doors, his own life and work was itself a door opener.

It would be a mistake to label Van Peebles’ achievements as only an African American inspiration, though his presence and impact as a pioneering Black artist is profound. He was simply avant-garde as a director, and his vision and DIY directing style, which gave him a commercial hit, had a major influence on Hollywood film in general, beyond the narrower discussion of race. A low-budget film that becomes commercially successful (think of films such as Juno or The Blair Witch Project) is a familiar concept now, but Van Peebles was arguably the first to do it outside of the major studio system, and he did it decades earlier, with the highly charged Baadasssss. It is hard to conceive of the innovations of 1970s cinema, and the alternative cinema that followed in the 1980s and ’90s, without Van Peebles.

I could go on, but for a quick example I can say that the swift and smooth violence of Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained does not exist in a world without Van Peebles. Spike Lee’s signature floating camera shots, and the charged public arguments his characters engage in around race, do not exist in a world without Van Peebles.

In the credits of Baadasssss, we’re told the film is “Starring: The Black Community,” and this credit is both novel and prophetic in that Van Peebles put urban African American lives and language, in all their grittiness and soul, on screen. In doing so, he awakened and inspired the political imagination of artists worldwide.

He certainly inspired me, and Van Peebles’s halo extends into the present and our lives here at OWU in yet another, and somewhat unexpected, way.

His son Mario, an established film director and actor in his own right, directed me in my first professional TV appearance. It was a tiny role, but it was my first, and I was the only African American aside from the junior Van Peebles on the set.

Van Peebles made a point to take some time and give me some coaching—something he not only did not have to do but wouldn’t have been expected to do, given the size of my small acting role. But I was deeply moved by that sense of care and concern with seeing excellent work happen.

It’s a feeling that I think endures at Ohio Wesleyan, and so I remember Van Peebles, the artist and artist nurturer that he was, as we all should: with great pride and endless appreciation.

By Brian Granger, assistant professor of theatre