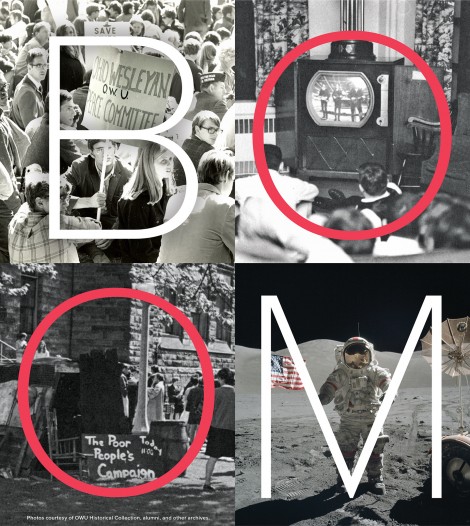

When the Boomers Hit OWU

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’

“The Times They are A-Changin’” – Bob Dylan, 1963

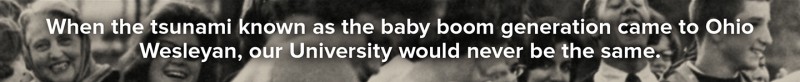

Five decades have passed since the day the first baby boomers (born in 1946) walked onto the Ohio Wesleyan campus. But memories of that tumultuous time for Ohio Wesleyan and the nation as a whole remain fresh for boomer Ed Haddock ’69.

The Richmond, Virginia, native says OWU was an “incredibly conservative place” when he first arrived on campus, a reflection of 1950s-America. But that began to change with the arrival of the baby boomers—Haddock among them—at the University.

The first baby boomers rolled onto the OWU campus, and within a short time, they had brought with them a new zeitgeist.

Much of it was due to the Vietnam War, which cast a cloud over campus, especially during Haddock’s junior and senior years. He says arguments over the war and changing social values caused a deep divide between juniors and seniors with more conservative views and freshmen and sophomores vocal in their opposition to the established way of doing things.

“There was no in-between,” says Haddock, who was student government president his senior year. “I’ve never been in a situation where there were such clearly defined value systems. It would not have been more conspicuous even if it had been spray-painted on the wall in different colors.”

Students turned up the volume on just about everything affecting their lives—Vietnam, the military draft, civil rights, rock ’n’ roll, drug use, and the beginning of the women’s movement. And they got bolder in pushing for changes to longstanding Ohio Wesleyan policies such as curfews for female students, restrictions on living off-campus, and drinking at University-related functions. Some also pushed for an end to de-facto bans on minority students pledging sororities and fraternities.

While not always successful in getting their way, Ohio Wesleyan students in the 1960s established a lasting legacy at the University, says Tom Tritton ’69.

“It served as a transitional period from the passivity of the ’50s to a much more dynamic, open, and questioning society that continues to this day,” he says. “It became permissible for students to challenge authority and confront things they saw as wrong. That was unlike past generations when you just went along with the program and didn’t say anything.”

Haddock believes the baby boomers who followed his OWU class had a major impact on the University.

“They brought to campus a very different culture than what had been there before,” he says. “It was led by the Vietnam tsunami and swept across Ohio Wesleyan and campuses in the rest of the country. The impact was very profound.”

Age of Aquarius

The changing times at Ohio Wesleyan in the ’60s are addressed in the book Noble Achievements: The History of Ohio Wesleyan from 1942 to 1992. Published as part of the University’s sesquicentennial celebration, the book was written by a number of faculty members and administrators and edited by Professor of Philosophy Bernard Murchland.

The changing times at Ohio Wesleyan in the ’60s are addressed in the book Noble Achievements: The History of Ohio Wesleyan from 1942 to 1992. Published as part of the University’s sesquicentennial celebration, the book was written by a number of faculty members and administrators and edited by Professor of Philosophy Bernard Murchland.

The book notes that student unrest related to the Vietnam War was just part of “a wide panorama of societal change” in the late ’60s. It included the Civil Rights Movement, the spread of rock ’n’ roll, and the beginning of the women’s movement.

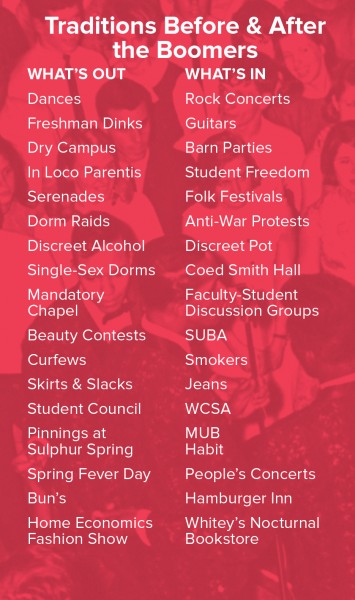

With the influx of baby boomers, the ’60s became the polar opposite of the tranquil ’50s, the book states, noting “traditions were scorned, rules were perceived as superfluous,” and students no longer went along with the idea that the University “should fulfill the role of rule-maker, enforcer, guardian, and protector of students.”

Much of the acrimony was fueled by student demands for changes in housing policies, including elimination of the rule that forbade men and women from visiting each other’s residence hall rooms. OWU’s official but often-broken prohibition on alcohol at University-related functions was under fire as well.

Students also began to voice their concerns on the draft, racial discrimination, and the Vietnam War. In 1966, 15 students from the local chapter of Students for a Democratic Society protested a Selective Service qualifying exam in the Memorial Union Building (now the R.W. Corns Building). Later, pickets protested campus visits by recruiters from the Marine Corps and Dow Chemical Company, maker of napalm used in U.S. attacks on targets in Vietnam.

Students in the 1960s established a lasting legacy at OWU, moving from the passivity of the ’50s to a much more open and questioning society that continues to this day.

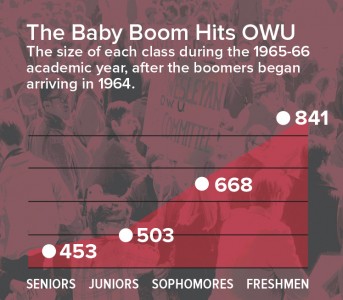

The scale of protests soon escalated. In 1968, about 250 Ohio Wesleyan students protested the war by marching through Delaware and sponsoring antiwar speakers on the lawn of Gray Chapel. In 1969, students organized a march prior to the Vietnam Moratorium demonstration in Washington, D.C. In addition, about 15 students staged a three-day “starvation strike” on campus in May that year, with a list of demands that included elimination of ROTC course credits, passage of a student bill of rights, and elimination of social restrictions.

The unrest reached a tipping point in May 1970 (at the same time as the Kent State shootings), when some 100 students took over the ROTC Building in protest of the escalation of the war. They also took part in more marches and stepped up their demands for participation in departmental meetings and on faculty committees.

Noble Achievements says the student protests and demands “caused serious but not insuperable difficulties for a flexible and liberal-minded faculty.” As a result, students were allowed representation on the University Board of Trustees, and student boards were taking part in evaluation of instructors, “furthering the democratic process in the governance of (the University).”

Several alumni from the late ’60s remember OWU administrators employing an even-handed approach in addressing student demands.

“They tried to manage the situation,” Haddock says, “and were careful not to restrict our freedom of expression, meetings, and demonstrations as long as they were not damaging anything.”

While its students certainly were engaged in the issues of the day, Ohio Wesleyan was spared the upheaval and violence seen at many other universities in the ’60s, says Professor Emeritus of History Richard Smith. He joined the faculty in 1950, retired in 1986, and remains part of the University community.

“There were no overturned cars, broken windows, or riotous behavior,” Smith says. “Part of it was we kept them working, writing papers and working in the lab. We demanded quality from them.”

He says Ohio Wesleyan students of that era continued to expect to receive a first-rate education as they pursued their goals of launching careers in law, medicine, government, science, and other fields.

“Their parents were behind them, too,” Smith says. “Wesleyan was able to stay on course.”

You Say You Want a Revolution

Ohio Wesleyan in the ’60s was still very much a place where in loco parentis was the order of the day, says Jean Fitzwater Bussell ’69. That meant a curfew for women, a ban on visiting the dorm rooms of the opposite sex, and no drinking on campus.

“It wasn’t until the early ’70s that the University went to a much more socially liberal set of practices on campus,” she says. “The revolution took a little longer to get to Ohio Wesleyan.”

As it is today, Ohio Wesleyan in the ’60s was a place where students received an education, both inside and outside the classroom, which would prepare them to make a difference in the world. For Bussell, the four years at OWU helped her realize a long-held dream—one held by many baby boomers.

“I wanted to be a social worker and change the world,” she remembers. “What Ohio Wesleyan did for me was to make me aware of what that meant.”

Bussell took a social work practice course with a field experience in which she worked with Delaware County families living in poverty and an urban sociology course in which she and classmates spent a week in inner-city New York.

In addition, the national events of the day, especially the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy, sharpened her thinking about the future and making a difference.

“There were so many things that happened while we were at Ohio Wesleyan that have affected our culture since then and hopefully prepared us to deal with it,” says Bussell, who went on to a long, impactful career in social services. “It was an amazing experience.”

A Change Is Gonna Come

Alumni from the mid- to late-1960s say Ohio Wesleyan was not a diverse place then, with only a small number of African-American and foreign-born students enrolled. It remained that way through the end of the decade, with a brochure produced by the Student Union on Black Awareness (SUBA) in 1970 noting 97 percent of the student body was white.

Racial segregation in Greek life that prevented Black students from pledging sororities was still in place at OWU in the early ’60s. That began to change in 1964 when Diane Petersen ’66, a black student from New Jersey, pledged Delta Delta Delta at the urging of friends from her dorm and classes.

“While some members of the sorority guessed that pledging an African-American might raise a few eyebrows,” Petersen recalls, “most never even thought about it. They simply wanted me as one of their sisters.”

Unfortunately, officials at the Tri Delts national headquarters in Texas did not see it that way. Nor did members of some chapters in the South, calling the Ohio Wesleyan chapter an embarrassment for pledging a Black student.

Petersen says the national office began scrutinizing the Ohio Wesleyan chapter’s records, looking for reasons to put it on probation and prevent it from initiating pledges into membership. But OWU President Elden Smith intervened on the chapter’s behalf with the Tri Delts national office, allowing Petersen to be initiated in the spring of 1965.

“President Smith was simply a prince through the entire episode,” she says. “I will never forget his constant support, encouragement, and empathy.” His stand against segregation in OWU’s Greek system became so emphatic that he wrote to the national offices of all sororities and fraternities active at the University, demanding they adopt a nondiscrimination clause in their bylaws or be expelled from campus.

But Petersen says OWU’s sororities still were slow to admit African-Americans and other minorities. “What happened to me was significant, but it didn’t mean the floodgates were open,” she says.

She also remembers rising awareness among students about the Civil Rights Movement during her years at OWU. That awareness continued to grow after she graduated when black students began to push for change on campus.

A watershed moment occurred in 1968 when SUBA was founded to support African-American students and enrich cultural understanding at the University. That was also the year when the Student Committee on Race Relations presented 12 suggestions to the administration on ways to improve diversity on campus. The requests, many of which eventually were adopted, included a center for African-American social activities, a Black counselor on the admissions staff, more Black faculty members, an African-American on the Board of Trustees, a Black history course, and a “positive recruiting attitude” to increase OWU’s minority enrollment, according to reports in The Transcript, the student newspaper.

R-E-S-P-E-C-T

The national women’s movement was in a fledgling stage in the ’60s, but expectations and opportunities for women were beginning to change, says Ann Tarbutton Gerhart ’69.

During her time at OWU, women generally were not encouraged to go to law school. But Dean of Academic Affairs Allan Ingraham urged her to apply and even called several law schools to help her gain admission. She accepted an offer from the University of Cincinnati and went on to a successful career as an attorney.

Gerhart also received encouragement from her advisor, English Professor Libby Reed, and Mildred Newcomb, the Mortar Board advisor. In addition, Gerhart was especially inspired by two of her sorority sisters at Kappa Alpha Theta—Barbara Brill Brown ’66, who went to Thailand in the Peace Corps and then to law school, and Barbara Hartley Schlachter ’67, who became one of the first women ordained to the Episcopal priesthood.

“In a time when many young women were only beginning to think beyond the immediate goal of marriage and family, role models were very important,” Gerhart says.

Petersen says cultural biases in the mid-1960s still steered women to careers in teaching, nursing, and administrative assistant work. But as the boomers hit campus and the number of female students grew, hope and encouragement also grew for OWU women with big dreams. Petersen, for example, was inspired by Professor Barbara Tull in the speech department.

“She was a model for me in terms of what women could accomplish,” says Petersen, who went on to a career as a physician and surgeon. “She showed me that if you can conceive it and believe it, you can do it.”

What Are We Fighting For?

While civil rights and women’s issues were gaining attention, the war in Vietnam was the biggest thing on the minds of most men of the ’60s at Ohio Wesleyan. Their futures and even their lives hinged on the draft and student deferments to keep them from being inducted into the armed forces.

Tritton remembers having helped set up a group that counseled students on the draft. He was also one of the organizers for several peace demonstrations on campus, and his name appeared in The Transcript as a spokesman for the Ohio Wesleyan Peace Committee, whose efforts included OWU’s participation in an international fasting movement against the Vietnam War.

Tritton says his four years at Ohio Wesleyan changed his view of the world and led to an idealism that valued peace, nonviolence, fairness, justice, and equality for all. It helped position him to embark on a remarkable career as a cancer researcher, academician, president of Haverford College, and chair of the OWU Board of Trustees.

Part of Tritton’s outlook was shaped by the fact that he and his classmates watched nightly as network newscasts reported on the escalating number of U.S. soldiers killed in Vietnam and campus protests against a war whose purpose was unclear to an increasing number of Americans.

Haddock says he opposed the war and felt the United States had no reason to be in the conflict. But he also thought OWU was not the place for antiwar marches and demonstrations.

Haddock says he opposed the war and felt the United States had no reason to be in the conflict. But he also thought OWU was not the place for antiwar marches and demonstrations.

“My point was that’s not why we were at Ohio Wesleyan,” he says. “I felt we were there to become equipped with a voice so we could have an impact on the world (after college) rather than to get bogged down in rejecting the positive things going on at our university. We were there to get on with our education and careers and to change things that way.”

Haddock has done that during a career filled with accomplishments as an attorney, business executive, and cofounder of Full Sail University, which offers degree programs for the entertainment industry, media, arts, and technology.

Tom Palmer ’69 remembers his undergraduate years as a time when OWU students tackled issues, including Vietnam and race issues, in a questioning yet productive way instead of “striking out” or dropping out.

He also says the shift in how students viewed the world did not affect the tight-knit bonds they had with faculty members. Palmer still speaks fondly of playing in a basketball league with professors and the University chaplain and how faculty members challenged students to think independently.

Good Vibrations

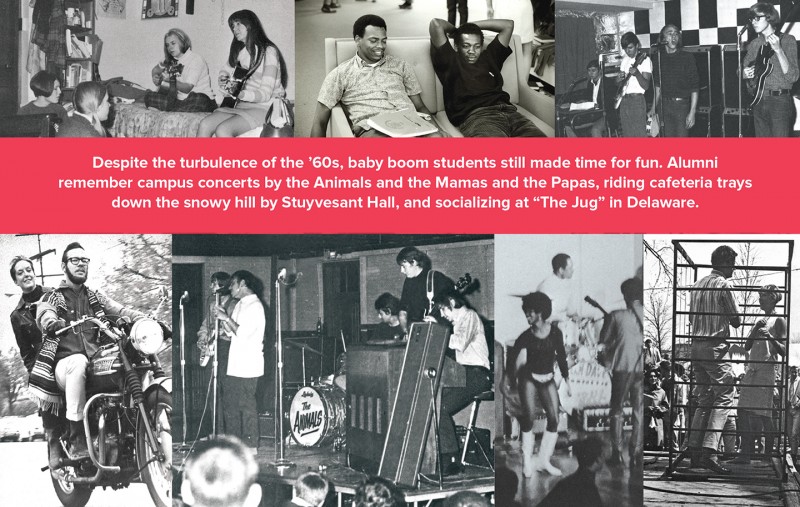

The ’60s at Ohio Wesleyan may have been filled with angst about Vietnam, civil rights, and feminism, but baby boom students, like the students who preceded and succeeded them, still made time for fun and games. Alumni from the late ’60s remember attending campus concerts by the Mamas and the Papas, Paul Revere and the Raiders, and the Animals, riding cafeteria trays down the snowy hill by Stuyvesant Hall, Homecoming in the fall, Monnett Weekend in the spring, sorority-fraternity dances, football and basketball games, and socializing at “The Jug” in Delaware.

But most important, Gerhart says, were the enduring friendships made during those years. Indeed she still meets annually on Long Island with about 10 of her OWU friends.

Palmer says his interactions with faculty members and his broader experience at OWU have served him well, including in his career as an attorney and civic leader in Toledo, Ohio. For him, that’s the lasting legacy of having been among the first baby boomers to graduate from the University.

“I look at Ohio Wesleyan as having been a wonderful experience,” he says, “because it gave me the opportunity to grow at the right pace and motivated me to continue to grow in life. I’m grateful for that and regard it as a gift.”

Other alumni see it that way as well.

“For me, it was my liberal arts education and how that prepared all of us so well for life,” Petersen says, “and then going back for a reunion and seeing how successful everyone was in their lives—and not just financial success.”

Gerhart adds, “Every generation has had to deal with changes, and our alma mater has held our hand the whole time. It has also grown and changed along with us. But the core values—intellectual curiosity, personal tenacity, service to others, and respect for all people—have remained.”

Jeff Bell is a freelance writer in Westerville, Ohio.