Contact Information

Dr. Barb Bird

Ohio Wesleyan University

61 S. Sandusky St.

Delaware, OH 43015

E bjbird@owu.edu

Written by Paul Dean, Professor in OWU's Department of Sociology & Anthropology

November 2025

Key takeaways from this article:

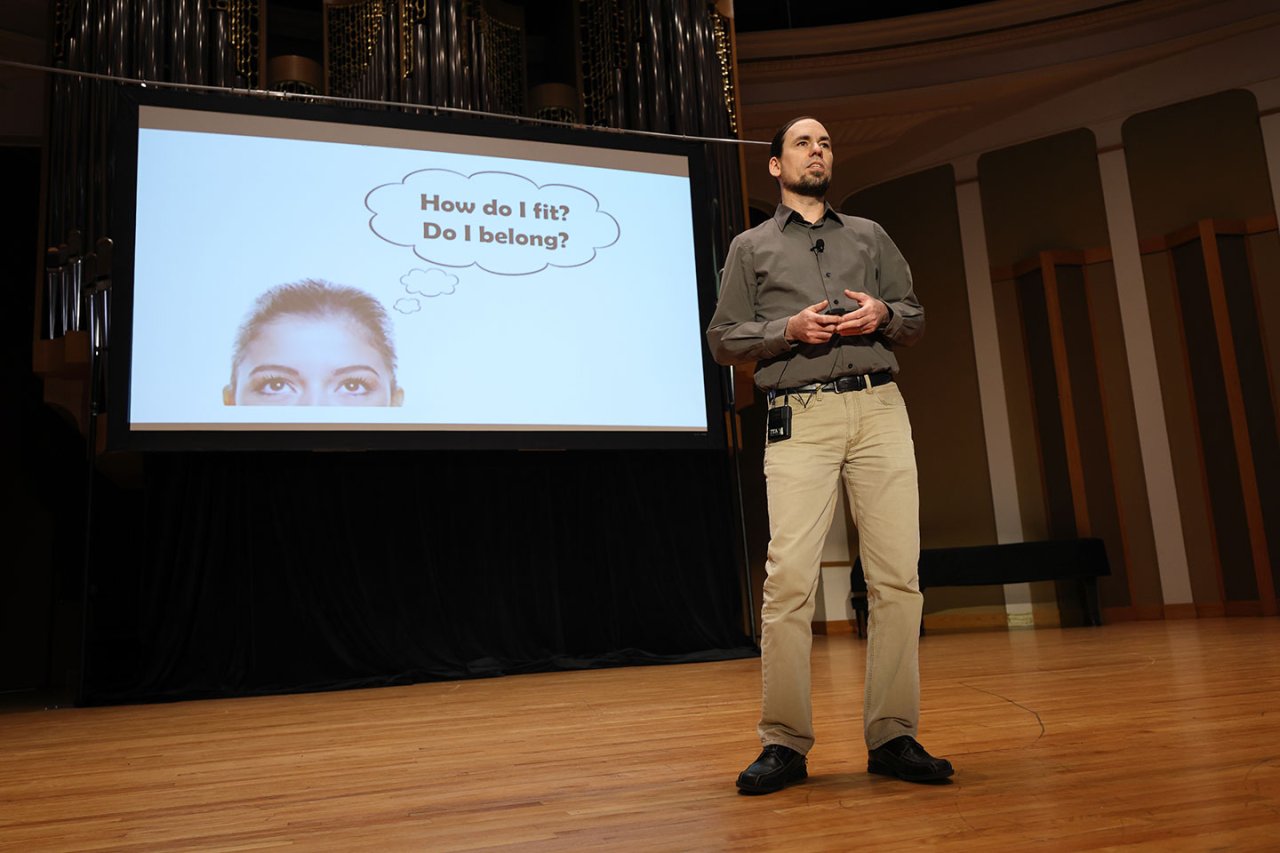

For first-gen students, higher education promises a pathway to a more secure and meaningful life full of opportunity. But colleges and universities leave something important out of the story. When first-gen students enter our college campus or classroom, there is a set of new and unwritten rules for how to speak, behave, and interact. It can evoke overwhelming feelings of alienation and imposter syndrome, with students often blaming themselves for the challenges they face.

Supporting first-gen students requires that we understand the differences between working-class and middle-class cultures, which I outline in my book, Class Cultures and Social Mobility. For example, class shapes how we talk and what we talk about, how we dress, our tastes, what we value, and how we relate to others. People in the working class are more group-oriented, they value hard work and authenticity, and their children in the working-class grow up to be more deferential to authority figures. People in the middle class have a strong sense of individuality, they value self-actualization and achievement, and their children are taught to advocate for themselves. There is nothing inherently better about working-class culture or middle-class culture.

Supporting first-gen students requires that we understand the differences between working-class and middle-class cultures, which I outline in my book, Class Cultures and Social Mobility. For example, class shapes how we talk and what we talk about, how we dress, our tastes, what we value, and how we relate to others. People in the working class are more group-oriented, they value hard work and authenticity, and their children in the working-class grow up to be more deferential to authority figures. People in the middle class have a strong sense of individuality, they value self-actualization and achievement, and their children are taught to advocate for themselves. There is nothing inherently better about working-class culture or middle-class culture.

For starters, students encounter a hidden curriculum, or values, dispositions, attitudes, and expectations that schools have for students but are not usually communicated. Students are expected to know how to navigate campus resources, to ask for help when they need it, and how to engage in academic discussion. When these elements remain hidden, we create barriers for students.

Furthermore, middle-class cultural biases can lead us to misinterpret WCFG students. For example, our WCFG students may have been taught to listen to authority figures and not talk back, so we might misinterpret their lesser participation in class discussions as a lack of preparation. WCFG may believe that being a responsible student means to figure it out themselves and not burden the instructor, so we could confuse their not asking for help as a lack of motivation. They have been taught to speak more concretely so we might misperceive them not using abstract concepts as a lack of ability.

The culture in which they were raised does not fit with the culture in which they increasingly find themselves. As a result, first-gens can experience imposter syndrome and the sense that they do not belong.

In an ongoing research project, I outline a two-pronged approach on how to best support WCFG students:

Without a complementary strengths-based approach, we risk devaluing WC culture, alienating WCFG students, reinforcing the advantages for middle-class continuing-generation students, and perpetuating unequal educational outcomes.

An effective first-gen pedagogy applies the two-pronged approach throughout our courses and interactions with students. The table below offers concrete examples that you can implement immediately and are supported by research.

| Build Bridges to MC Cultural Capital to Overcome Barriers | Leverage Existing WCFG Strengths | |

| Assignment Examples | WCFG students are more intimidated by professors, more likely to believe that asking professors for help is a burden to instructors, and are less likely to advocate for themselves (Lareau 2011; Yee 2016). We can normalize help-seeking behaviors by creating an office hours assignment requiring students to meet with you, perhaps to discuss an exam or another assignment. If possible, cancel a class to make time for meetings in your busy schedule. | When students are asked to reflect on their values or their strengths as FG students, research shows they perform better on academic tasks and earn higher GPAs (Bauer et al 2025; Harackiewicz 2014). Consider assigning an identity-reframing activity (or a values affirmation activity) or conduct one in class to help motivate students through an awareness of their values and strengths. Designing assignments that connect students' life experiences to course content further helps engagement. |

| Engagement & Communication with Students | The hidden curriculum includes expectations for how students should interact with professors and staff. Expose the hidden curriculum by providing resources on why and how to use professors' office hours; normalize asking for help academic support staff (Davis 2010). Create less formal opportunities for students to get to know you better. | FG students are often highly motivated and feel they must work harder than others to succeed (Bauer et al 2025). When communicating with students, help them orient their efforts using this research to frame feedback with a growth mindset, which has additive effects for WCFG students (Canning et al. 2024). |

| Classroom Dynamics | The hidden curriculum also includes expectations for academic debate, identifying key concepts, and study skills. Reveal these norms and help students build skills by providing and explaining rubrics for academic discussion and debate or how to identify important concepts, take notes, etc. (Davis 2010). | WCFG students are socialized into more group-oriented than individualistically-oriented norms, and less likely to be comfortable working across status hierarchies. Draw upon their strengths using deliberative interdependence by building on prosocial norms and having small in-class group activities or team-based projects (Estefan et al. 2023). |

| Syllabus and Course Design | First-gen students may not understand the purpose of a syllabus, especially if it incorporates highly academic language that gets in the way of communicating its function and uses. We can help students understand the course and expectations by evaluating the complexity of syllabus language, and when possible, use more plain language. Using learning-focused language will also increase student participation and guide appropriate expectations (Wheeler et al. 2019). | WCFG students believe they have to be responsible for themselves, but "unlike middle class students who interpreted that responsibility as reaching out to seek help, FG students interpreted the responsibility as being on their own to succeed" (Yee 2016). The strength for FG students here is their focus on following instructions in course materials closely. We can leverage this by providing students with highly structured courses, which Beck and Roosa (2020) found to increase FG student engagement. |

| Modeling & Mentoring | First-generation students are more likely to experience imposter syndrome. Openly discussing your own experiences with imposter syndrome or challenges as a student can help students to feel a sense of belonging and understand that their experiences are not just about them (Maclean 2022). They too can build the skills necessary to succeed. | Recognize that WCFG students' higher deference to authority/experts means they will often take your comments to heart (Lareau 2011). Through modelling academic habits and identifying goals, you can help FG students see possible futures and support them in developing plans to make it happen. |

One of the great things about the strategies outlined here is that they are shown to have positive effects for all students (or at worst, effects will be neutral for dominant groups). You don't actually have to know who your FG students are to better support them. By adopting pedagogies supporting first-gen students, you are actually helping all students.